Category Archives: Books

The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore: Oscar Winning Short Animation

This is the 2011 Oscar winning short animation, ‘The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.’ It’s the first film from Moonbot Studios in Shreveport, Louisiana. It was co-directed by William Joyce and Brandon Oldenburg

The film is also an iPad app that combines animation with an interactive picture book narrative.

On Reading Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow – Part 1

Every word in Thomas Pynchon’s deranged dance macabre, ‘Gravity’s Rainbow,’ seems, like HTML, to link out to some other subject. The book seems for me to exist in-between worlds, barely attached to this one while trying desperately to connect us with another fuzzily glimpsed, just-hinted, vague world, suggested by pure chance connections between ideas and events here on a fractured and demented earth. I’m barely one hundred and sixty-five pages into this book and I’m reacting for it and against it in nearly equal measure. It’s a goddamn blast. It’s also a motherfucking bitch. Every page of it so far mentions some kind of rocket trajectory, launch pad, descent, explosion or blast of light. Everyone in the book seems to be living out one debauchery or another while all the time expecting to be blown away in bits, perhaps even looking forward to it. Death, for Pynchon, seems on the surface like fun. The book almost makes a mockery of dark humor, of dying. It’s as if Pynchon wants to give the finger straight into the yawning mouth of death’s favorite century.

Every word in Thomas Pynchon’s deranged dance macabre, ‘Gravity’s Rainbow,’ seems, like HTML, to link out to some other subject. The book seems for me to exist in-between worlds, barely attached to this one while trying desperately to connect us with another fuzzily glimpsed, just-hinted, vague world, suggested by pure chance connections between ideas and events here on a fractured and demented earth. I’m barely one hundred and sixty-five pages into this book and I’m reacting for it and against it in nearly equal measure. It’s a goddamn blast. It’s also a motherfucking bitch. Every page of it so far mentions some kind of rocket trajectory, launch pad, descent, explosion or blast of light. Everyone in the book seems to be living out one debauchery or another while all the time expecting to be blown away in bits, perhaps even looking forward to it. Death, for Pynchon, seems on the surface like fun. The book almost makes a mockery of dark humor, of dying. It’s as if Pynchon wants to give the finger straight into the yawning mouth of death’s favorite century.

Things I notice so far about the book: Rockets of course. Everywhere and in every mind of the characters. It’s all about predicting bomb hits and finding the rockets. People want to understand how one of the characters can possibly manage to have sex in various locations just prior to those spots being bombed into oblivion by German V-2 rockets. The books seethes with sexual excitement that’s a death-wish. I also notice that Pynchon is associating Hansel & Gretel, the forest and the witch’s oven with Germany and the events of World War II. The Holocaust is looming over this book on every page. There are constant mentions of cause and effect, how it operates and whether it might be possible to break out of its logic. Can a rocket attack be sensed before it even hits? Psychological early warning system. Brain radar. Statistical analysis for making predictions.

Imagine a missile one hears approaching only after it explodes. The reversal! A piece of time neatly snipped out…a few feet of film run backwards…the blast of the rocket, fallen faster than sound–then growing out of it the roar of its own fall, catching up to what’s already death and burning…a ghost in the sky…

Quite a few references to film in this book so far up to page one hundred and sixty-five.

What could be more paranoid than a constant worry about bomb rockets? The book seems like a grotesque exaggeration at first. But that’s the joke I think. It’s actually an understatement and proves paranoia to be the most well-placed and logical mental operation in a century during which people were dug into trenches and told to march toward each other like polite firing squads. A century in which men marched millions of people into gas chambers and pushed them through ovens. A century in which entire cities were blown off the face of the planet while the citizens were out shopping for groceries. Pynchon seems like an author who is not afraid of any of it. He’s like a guy laughing at the scene of a traffic accident. Or photographing it like Warhol did. And the book’s laugh-in-a-sort-of-half-shocked-way funny. Here’s a bit from a funny scene where a guy visits a nurse he wants to sleep with but must endure a lengthy sit-down with an older woman patient who wants to share her candy:

Under its tamarind glaze, the Mills bomb turns out to be luscious pepsin-flavored nougat, chock-full of tangy candied cubeb berries, and a chewy camphor-gum center. It is unspeakably awful. Slothrop’s head begins to reel with camphor fumes, his eyes are running, his tongue’s a hopeless holocaust. Cubeb? He used to smoke that stuff. “Poisoned…” he is able to croak.

“Show a little backbone,” advises Mrs. Quoad.

“Yes,” Darlene through tongue-softened sheets of caramel, “don’t you know there’s a war on? Here now love, open your mouth?”

It’s funny, no? But it should also set off sparks off recognition in your head that link up with gas chambers. You just can’t trust Pynchon to be genuinely funny. He’s watching you laugh and getting ready to slit your careless throat. No wonder Pynchon uses a secret identity. He’s dangerous. He seems slightly criminal. This guy loves conspiracies. He must have some really excellent ideas about who killed Kennedy. I mean he’d probably say Oswald did it, but it’s why Oswald thought he was doing that makes it interesting.

I love it when authors hide their identities. Pynchon has been effectively doing this for about fifty years now. This reminds me, as all secret identities do, of Batman.

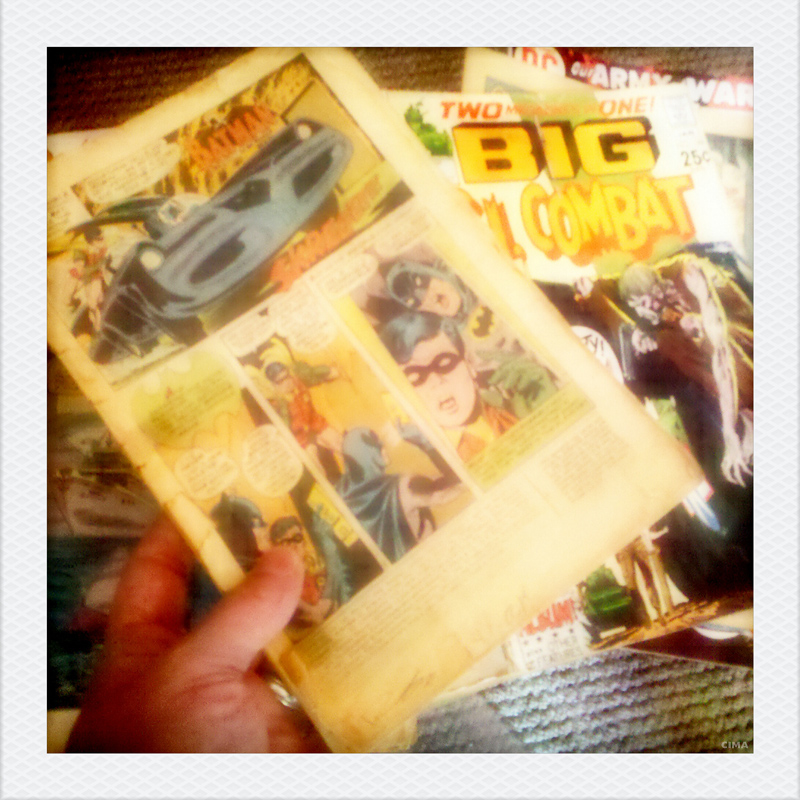

Here’s my ancient and torn copy of a Batman giant issue from 1969. Down in the lower margin there I wrote ‘fuck.’ I’m not sure why I would have done something so charming to a Batman comic. I must have been practicing my favorite words or something. What does an old comic book have to do with Pynchon? I don’t really know but it seems to fit. In fact, comic artist Frank Miller did the cover for the recent Penguin edition of Gravity’s Rainbow. That’s the copy of the book in the first photograph above. Behind the book in that photo is a computer screen showing a drawing by artist Zak Smith who did a thing he called ‘Illustrations for Each Page of Gravity’s Rainbow.’ It’s been shown at the Whitney Museum and you can buy it in book form.

Here’s my ancient and torn copy of a Batman giant issue from 1969. Down in the lower margin there I wrote ‘fuck.’ I’m not sure why I would have done something so charming to a Batman comic. I must have been practicing my favorite words or something. What does an old comic book have to do with Pynchon? I don’t really know but it seems to fit. In fact, comic artist Frank Miller did the cover for the recent Penguin edition of Gravity’s Rainbow. That’s the copy of the book in the first photograph above. Behind the book in that photo is a computer screen showing a drawing by artist Zak Smith who did a thing he called ‘Illustrations for Each Page of Gravity’s Rainbow.’ It’s been shown at the Whitney Museum and you can buy it in book form.

It’s strange how much I’m enjoying this book because I hated ‘Ulysses’ by James Joyce. I think Pynchon snagged some stuff from Joyce. He even resorts to script format for some portions of the book the way Joyce did. But I only like the first part of Ulysses which takes place on top of a tower and has a character shaving. I also enjoy the part about Bloom in the park watching the girl’s underpants. But that book suggests to me that Joyce was mentally ill. With Pynchon I get the feeling that the world and everyone in it is mentally ill.

There’s also a definite connection between Pynchon and William S. Burroughs. In fact I wouldn’t be surprised if they were the same person. But that’s impossible. They both like secret organizations of scientists or researchers though. They share this fascination with science gone crazy and used to control minds – populations. But Pynchon is a better writer – less concerned with gimmicks. His language is a constant beauty which is the great antidote to his hilariously murderous world view. His entertaining and wildly connecting sentences indicate to me that Thomas Pynchon is an optimist. But, as with Joyce, I find myself constantly shutting the book and wondering, ‘How did he do it?’ How for fuck’s name did this guy not only maintain a secret identity but accumulate so much esoteric knowledge in the late sixties so as to be able to jam-pack every single sentence in the bloody book with some reference or other to some event or other that no sane person would ever have heard of in a lifetime? What the hell is going on in this man’s mind that allowed him to achieve Google knowledge density in 1973?

For all the good it might do anyone, I’ll keep reading the book and make a few more posts about it. I tend to relate work like Pynchon’s to my own video work. It’s something to do with the density of thought and imagery. It’s always good to read solid evidence of someone being crazier than you are so that you can get down and work at your own stuff with a little less embarrassment.

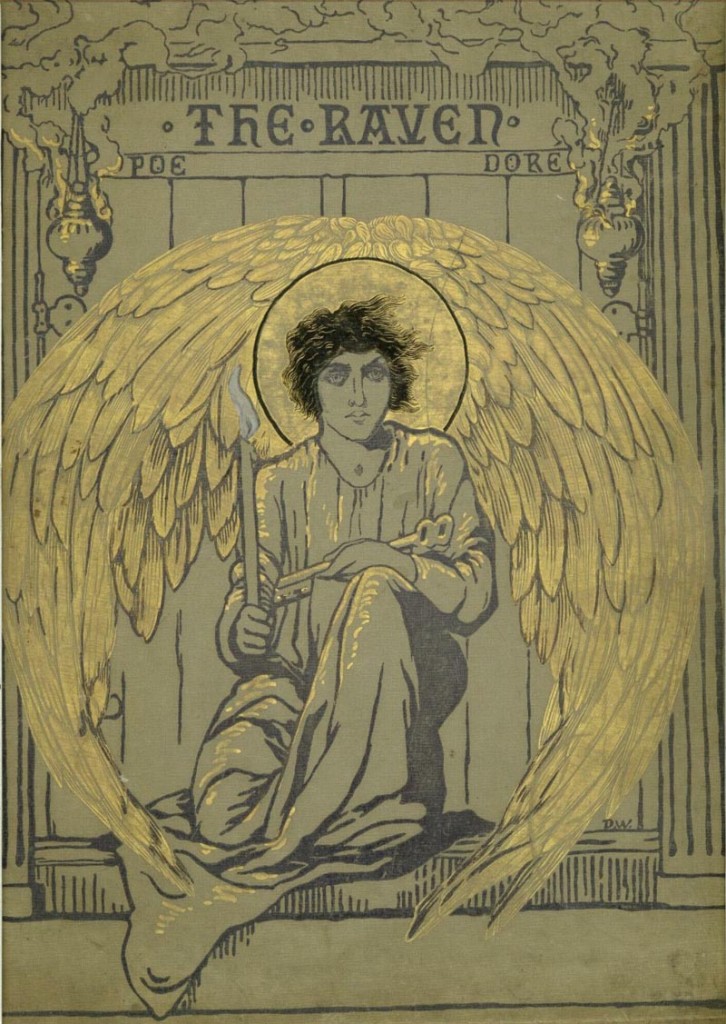

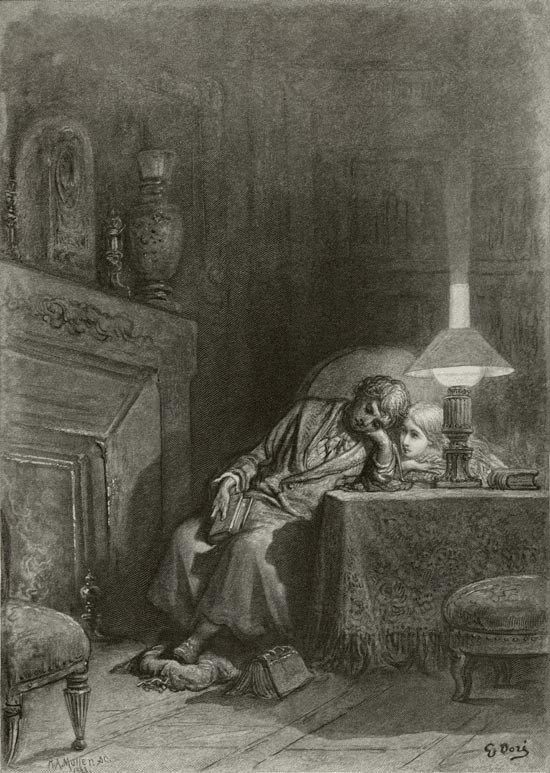

Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Raven’ Illustrated by Paul Gustave Doré

This incredibly beautiful edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Raven’ was published in 1884 with illustrations by Paul Gustave Doré. Click on the images to see full sizes.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore–

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“‘Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door–

Only this and nothing more.”

Animation: The Story of the Book

One of the submitters to my Vimeo short films group, Robert Lyons, sent this short French stop-motion film in. He worked as the directory of photography on it. The director was Delphine Burros. It’s about a librarian who opens a magical and evil book.

BOMB: A Manifesto of Art Terrorism

Artist and filmmaker Raymond Salvatore Harmon has written an inspiring and thought-provoking book that insists on changing the way art is perceived and approached by artists, viewers and the ever-problematic gallery world. Harmon presents several stories of his own brushes with law enforcement that are both funny and rather harrowing. He consistently recommends behaving as if you have every business being exactly where you are even if you have no permission to paint the front of a building. Confidence and apparent command of a situation will often get a clever artist out of a jam. Harmon is a very likeable guy and I can’t imagine there would be too many police all that interested in arresting this particular artist whose work always seems to have good intentions behind it.

Artist and filmmaker Raymond Salvatore Harmon has written an inspiring and thought-provoking book that insists on changing the way art is perceived and approached by artists, viewers and the ever-problematic gallery world. Harmon presents several stories of his own brushes with law enforcement that are both funny and rather harrowing. He consistently recommends behaving as if you have every business being exactly where you are even if you have no permission to paint the front of a building. Confidence and apparent command of a situation will often get a clever artist out of a jam. Harmon is a very likeable guy and I can’t imagine there would be too many police all that interested in arresting this particular artist whose work always seems to have good intentions behind it.

Here’s an important quote from the book:

Ultimately, corporations play the biggest part in designing our modern world. Corporations sell goods, make cars, pump oil and make medicines. They design city planning and develop urban neighborhoods in order to make profit. They create ghettos to house those people that they pay so little they are unable to afford to live anywhere else. Making them exist at the most nominal part of financial need, particularly outside of the white picket fences of the 1st world nations.

Yet, in the darkness of the city night there are those that go out and change the urban landscape without planning permission of a performance license. These people vary in intent and talent but they collectively do what they do against society and against the law.

I like this book. I find it generally inspiring and agitating in the best possible way. However, I do have arguments with it. In general, I tend to prefer looking at street art that does not actually destroy or harm property. Artists who violate laws by gluing things on walls should I think be treated rather lightly. However, I can certainly imagine scenarios in which a business – even a corporate one – could be seriously harmed by the placement of street art on its walls. Not all corporations are British Petroleum. I don’t see any logical link between artistic statement and one’s attitude about a public or corporate wall. If art should in fact be more focused on the act of creation and viewing by the public without concern for how quickly the art is removed, as Harmon’s book suggests, then street artists should be content with painting their work on paper or cloth and hanging it from those corporate walls. Why is there a link between the making of an image and the destruction of a blank corporate wall? Why not make the art and preserve the blank wall?

Harmon has some harsh words for the art world that links itself inextricably with the art schools, identifying artists it likes, feeding them into a network of wealthy friends and collectors, creating an insular world of wealthy back slappers and promoters. You can see this world in operation all over New York and even in Los Angeles. However, I would point out that crony networks are notoriously good at finding and publicizing actual brilliance.

Elsewhere in the book, famed artist/street prankster Banksy is quoted as saying:

Remember, crime against property is not real crime.

Banksy is of course not someone I would want to be taking very seriously since it is more than likely that he is little more than an employee or creative group working at Urban Outfitters. Thankfully, one of Harmon’s stories about copyright leads right into an episode that reveals Mr. Urban… sorry… Banksy, to be just as copyright-obsessed as any corporation. Banksy is apparently working hard on a piece in model Kate Moss’s bathroom… you kind of get the picture?

You’d do much better reading this marvelous and good-natured jab-in-the-ribs art manifesto than paying attention to Banksy, that’s for sure.

Elsewhere in the book is a thoroughly amusing account of an assault on a major art world event that involves video cameras, dark suits and some very CIA-type stuff going on. Read it and enjoy.

Here is the entire book: